“Using this groove in the hand-rail as a directional device develops my confidence in wayfinding, even when I’m not accompanied by my dog.”

–Diane Bergeron, Accessible Design Expert. Diane Bergeron consulted extensively with Architect Ron Wickman when he was designing the space. Her input was invaluable.

AN ACCESSIBLE OFFICE SPACE

The architect’s essential task is to design paths and means of movement that are clearly organized and intuitively locatable.

When I was asked to design the office space for the Premier’s Council on the Status of Persons with Disabilities in downtown Edmonton, this became my challenge. Details like the handrail had to be perfectly honed as a directional detail for staff and visitors entering the meeting rooms and offices of varying sizes, support spaces or accessible washroom, all designed to accommodate as many people as possible.

The four grooves cut into the circumference of the handrail, set at 900mm (3’-0”) above the floor along the entire privacy wall indicate the location of doorways to adjacent cubicles. The handrail detail is unique to this office space, making it necessary for users to know the purpose of the grooves as a directional device.

The above image is an interior view of the waiting area highlighted by the curving privacy wall.

As one enters the office space, the most immediate feature is the tremendous spaciousness. The waiting area is extensive, highlighted by a curving division wall. The wall undulates upwards from the most public to the most private spaces in the office. To the east, directly off the foyer, an accessible toilet room in a circular shape amplifies the spaciousness. Meeting rooms, offices, and cubicles are comfortably roomy; nonetheless, it is secondary to the spaciousness that surrounds them.

The elements of wayfinding design—that is how people orient themselves in a space—make the office space uniquely empowering for its users. One-and-a-half-meter-wide squares are cut into the existing carpet at points where the user would need to make a decision to change directions using squares made of Marmoleum, a greener, more sustainable variety of linoleum. The color and texture contrast serve as wayfinding cues and assist people with visual disabilities to make positive and purposeful choices in movement. For people who are blind, the squares allow them to move about without the use of a cane or a guide dog. The vocabulary provided by the color and texture of materials, by decorative elements of walls and ceilings and by light, sounds and smells, is almost infinite.

This image is a floor plan of the office space for the Premier’s Council on the Status of Persons with Disabilities, located on the eleventh floor of the HSBC Building in downtown Edmonton. The orange and yellow Marmoleum squares act as color and textural contrast indicators in directional wayfinding, indicating the need for the person to change direction.

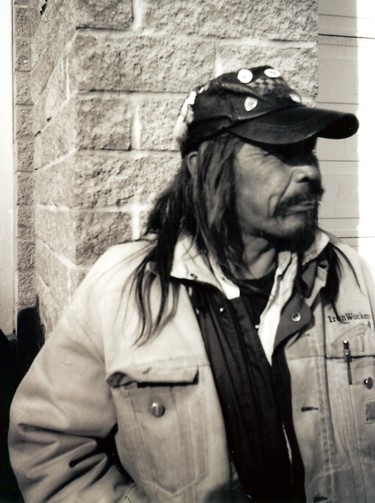

The image beside shows Diane Bergeron and her guide dog standing outside a cubicle space utilizing another directional device carved into the wooden handrail. I was confident in the task, but my friend Diane Bergeron gave me great insight into the way persons with visual limitations orient themselves in space and move around it, including enhancing the maximization of echolocation. Thanks to her intelligent questions, the office space, designed to accommodate

staff members like her who are blind or use wheelchairs, functions well.

In the world of design, many architects focus an inordinate amount of energy on the visual beauty of a detail. Completed with great effect it may indeed be very beautiful but its functionality matters not at all to the designer, his peers and the general public. An accessible design detail, however, must not only have beauty, it must also work functionally for all users. When an accessible design detail is completely wrong, it will indeed not only look dumb to everyone, it can also confuse users for whom it was intended.

An astute observer and a practical woman, Diane Bergeron was a tremendous asset to me while I worked on this project. She gave me great

insight into the way persons with visual limitations orient themselves in space and move around in it. She also often offered practical solutions to enhance echolocation as this capability is known. During design meetings, I had to be very detailed in my verbal descriptions about the office layout to convey my intentions, a practice which greatly benefitted everyone’s understanding of my design process and solutions.

The mandate given me was to design the new Premier’s Council space as the best example of good design possible, not simply focusing on good accessible design. This moves the focus away from just designing to accommodate persons with disabilities toward designing to accommodate everyone. Through the strategic placement of the functions, activities and elements that make up a building, and through the manipulation of space, light, color, texture and materials, architecture helps allow all users to make positive and purposeful choices for independent movement. It’s a given. Accessible Design then, is not just considering the individual pieces that make up the whole, but rather it is recognizing that the collection of pieces are all deeply interdependent.

The accessible toilet room that I designed is a focal feature in the overall design of the office space. Glass blocks allow for natural light to enter the washroom. The door’s kickplate is organically shaped, utilizing the same Marmoleum that is used in the flooring contrast pieces. Color contrast is also used inside the toilet room where the floor meets the wall. This allows people with low vision to identify the boundaries of the space. Ultimately, this space is a positive blend of function and beauty. What makes the space so beautiful is its functionality.